News and Insights

The Aging Elephant in the Room

February 12, 2024

The demographic choices of the last fifty years are catching up with us.

The make-up of the world’s population is changing very fast. Children alive today will see the number of Chinese and Koreans halve, and Nigeria become the second most populous country. Most countries will age rapidly. There are three possible ways to manage this new silver reality. All require much more thought than policymakers are currently giving to a world where the number of old and very old people is growing faster than the number of young people.

Three ways to adapt

We might get very lucky: artificial intelligence might take over a higher proportion of all work as the labor force shrinks and as lots of old people need more and more services. We might, but that is not what has happened in any previous technological revolution, as I explain below. AI may, though, solve the only problem that policymakers do worry much about: health could become more affordable.

There are only a few large areas of the world where the number of births is still well above two per couple. The young from those areas may need to move to places where many couples are having one child or none. Indeed, there may be a global competition for increasingly rare youth resources. It will require a radical shift in thinking about culture.

Neither of these mitigation approaches will be smooth or easy, so we need now to be focused on making every child we have as healthy and productive as she can be. We also need to think about how to keep the disenchanted elderly at work: they are mostly able to work for longer but prefer racking up debts for the next generation while they enjoy an unsustainably long retirement.

The aging world will soon come to dominate discussions about who pays what for health and much else. Those who think about it now will be best able to respond to the panic when it comes.

How we got here

Over the past fifty years, we have worried too much about overpopulation and not enough about shifting dynamics.

Fear of the consequences of overpopulation dates back at least to the Reverend Thomas Malthus, who started to publish his theories in 1798. Malthus argued that, however much technological progress might improve supply, exponential growth in population would eventually exhaust the world’s resources. Scholars still argue about where he was right and where he was wrong, but he certainly did not foresee our current reality of few children.

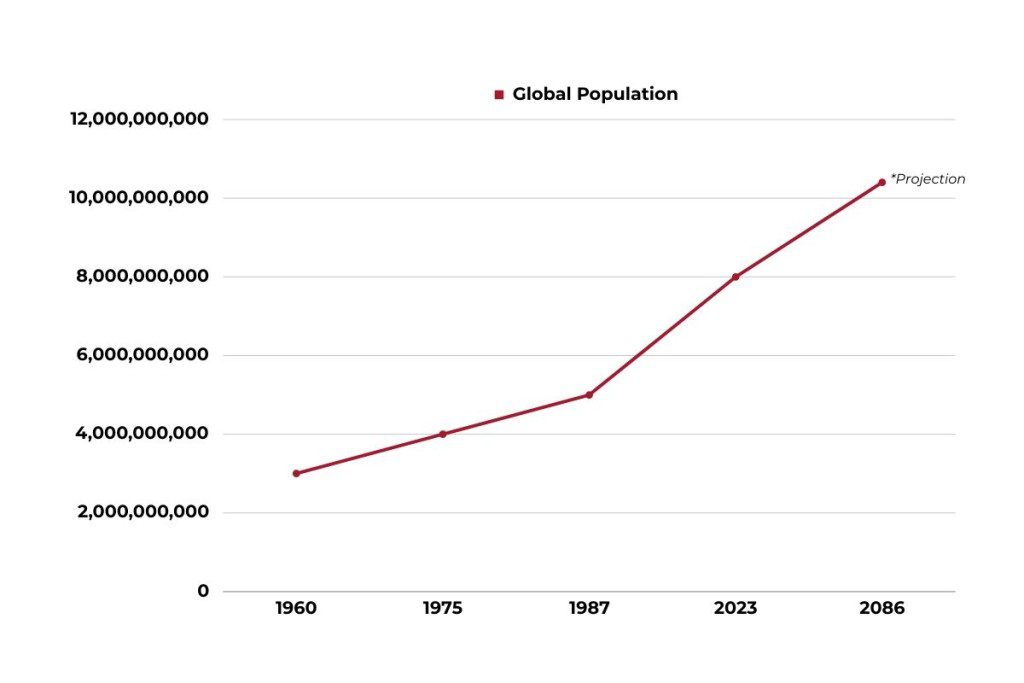

The big error in Malthus’s thinking was that population growth would be exponential until crises caused it to plunge. Malthus was thinking mostly about famine; Neo-Malthusians later pointed to an ecological collapse. In the second part of the last century, the rise in the world’s population looked terrifying. The Earth’s population was estimated at three billion in 1960; by 1975, it was four billion; by 1987, it was five billion. Today, it is eight billion, and the UN estimates that it will peak in 2086 at about 10.4 billion (another reputable forecast has a lower and earlier peak). That bolus of people in the second part of the twentieth century is the reason we now have such a rapid shift in the average age on the planet. When I first started working in the field in the late 1980s, some still thought Malthus might have had a point and that the spurt might actually be a long-term trajectory.

The shortcomings in Malthus’s reasoning were obvious, albeit in hindsight. Europe’s population growth was long over, and its pattern would be replicated in most of the world. The most charismatic of those who explained the process was Hans Rosling, a professor of international health at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. Rosling’s key theory was mainstream, but he explained it much better than most demographers. (I can’t begin to do justice to his genius as a communicator – have a look). “Only by raising the living standards of the poorest can we check population growth,” he said. Specifically, child survival was key to lowering the number of children that each couple decided to have. As parents see their children surviving and as women gain access to economic opportunities, population growth screeches to a halt. Rosling’s powers of persuasion about the ties between survival and a lower birth rate were a large part of what got Bill and Melinda Gates to focus so relentlessly on child health.

For the great self-regulating mechanism to work, couples, especially women, need to have the ability to make their own choices about how many children to have and when – a choice about fertility is also a fundamental human right for women. That means access to a range of family planning methods. A coalition of the fanatical, the misguided, and the evil have worked tirelessly since the 1950s to stop women from being able to make choices about their own fertility. The extraordinary sight of Vatican officials plotting with fundamentalist Islamists, African dictators and deluded radical feminists was, for me, the most abiding memory of the 1994 Cairo International Conference on Population and Development. (The Vatican thought its sincerely held beliefs should be imposed by law. The radical Islamists thought something similar. The dictators convinced themselves that large, poor, unhealthy populations would be a route to power. I never understood what possessed the radical feminists into believing that unplanned pregnancies would advance the rights of women)

Had the advocates of universal access to voluntary family planning won the day, hundreds of millions of women would have led better, happier lives and more children would have reached their potential in a manner that was often impossible in families too big for parents to support. Then and since, international efforts have had only limited success in meeting the gaps in family planning services

Had they done better, the global population would peak at a lower level, the demographic cliff edge would be less shear, and the climate crisis would be less severe. A decade ago, we worked with the Hewlett Foundation to promote policies based on voluntary family planning as one of the most cost-effective ways to mitigate climate change. I don’t think I have ever been so vilified or ostracized (and I was the head of communications for an AIDS charity in 1983!) No one was suggesting that women be forced to have fewer children, but that is how the debate was often heard.

The Cairo conference, those Hewlett-funded researchers and others working for women’s reproductive human rights have lived in the shadow of China’s coercive family planning policies and the short-lived attempts of Mrs. Indira Gandhi and her son to bring those policies to India in the late 1970s.

I escorted a group of Western journalists to China in the mid-1990s as part of a Rockefeller Foundation-funded project on reporting population issues. The reporters asked about punishments, fines and forced abortions for women who had more than one child. Our hosts at the State Family Planning Commission told us, “You have misunderstood. The state is happy to provide all health, education and food to the first child; families are simply asked to make a contribution to the costs of further children.” The officials were lying.

The draconian one-child policy brought China’s population growth down very fast, but it entailed massive social pressure and frequent abusive treatment of couples who tried to have second or, heaven forbid, third children. Fines, exile to rural areas and even forced abortions were common as overzealous local officials tried to meet national targets. It has also left China with a plummeting number of people entering the workforce in the years ahead.

We find ourselves in a world of extremes: some women are still forced to have more children than they want, while it is only in the past few years that most Chinese women have had the freedom to have larger families. Booming economies have led to falls as fast as China’s in countries with no hint of coercion. The net effect will be a fundamentally unbalanced world.

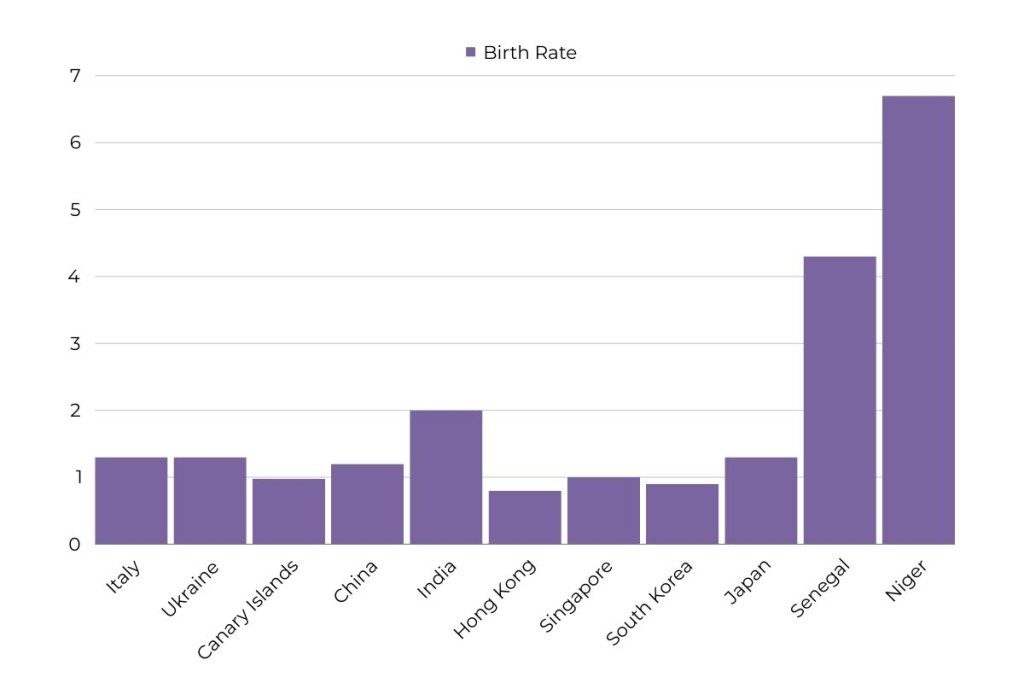

If each couple has, on average, 2.1 children, the population will remain stable. Globally, couples had 2.3 children on average in 2022. Both India (2.0) and China (1.2) are below the replacement level, as is most of Europe and all of North America. The native-born population is falling precipitously in countries and regions including the Canary Islands (0.98), Hong Kong (0.8), Italy (1.3), Japan (1.3), the Republic of Korea (0.9), Singapore (1.0) and Ukraine (1.3). Countries such as Hungary and Russia have introduced policies of social pressure and incentives to boost the birth rate, with limited success, as both are still well below the replacement level. Countries with high immigration do better in the short term, but the immigrants seem soon to conform to the fertility patterns of the native-born.

Nineteen of the 20 countries with the highest birth rates are in Africa (the exception is Afghanistan). Several countries in West Africa face very fast-growing populations: couples in Niger, for example, still have 6.7 children per couple. Even well-organized and relatively prosperous Senegal still has a total fertility rate of 4.3. Most of the countries with high population growth, though, are very troubled: the Central African Republic, Chad and Somalia, for example.

By 2100, one estimate suggests that China’s population will have fallen from 1.4 billion to 732 million; South Korea’s population will have halved. Nigeria will have risen from 206 million people to 791 million. Nigeria, already densely populated, cannot support 800 million people; China probably cannot function with 700 million; South Korea, almost certainly, cannot support itself with 24 million. By then, over a quarter of the world’s population will be aged over 65.

This older world will need help. The two most likely external sources are artificial intelligence taking the place of many human workers and immigrants taking the place of ageing ones. Help from within will involve making the most of all of the human resources in mature economies.

Can AI save Europe, China and Korea?

“You should worry more about the clerical, white-collar jobs than the physical [jobs]. A large number of them will get replaced. So the question is: ‘What jobs do you create to replace those?’” said IBM’s chairman and chief executive Arvind Krishna at the World Economic Forum in 2023. Respectfully, I don’t think he needs to worry

The Industrial Revolution, which began in England at the end of the eighteenth century, brought a massive shift from an economy centred on production in family units to a system based on salaries and factories. Blacksmiths and seamstresses did badly, but most became mechanics or machine operatives; some earned less, but many earned more. Many had to move to new regions. The Industrial Revolution happened alongside a steady rise in population, but there appears to have been little long-term mass unemployment.

Imagine the reaction if you had told someone in the 1950s that there would soon be very few ledger clerks, shorthand typists or local bank managers, but there would be lots of personal trainers, baristas and app developers.

The history of technological breakthroughs is that new jobs and needs replace those that are lost. Out-of-work lawyers will find jobs we haven’t imagined yet. So we can’t rely on AI to make up for Korea’s 50 percent drop in population.

There is likely to be one particularly important reshuffling of work. “When you get to medical school, all the complex math concepts, physics, and organic chemistry goes out the window. If there was one way to explain medical school, it was rote memorization.” wrote Kevin Jubbal, MD, in 2016. These recall and matching skills are exactly the ones that AI will make redundant. AI has already been shown to be better than British GPs at diagnosing and treating bacterial infections and better than Indian health professionals at spotting early-stage leprosy. AI is better than pubic health doctors at predicting which populations are at high risk of heart disease and better than many oncologists at predicting which cancer patients will have a recurrence. A wholly autonomous surgery robot outperformed American human surgeons in suturing as early as 2016.

Soon, AI will be better at almost everything doctors do other than talking to patients, and most doctors are not nearly as good at that as nurses. The average American physician earned about $350,000 per year in 2022. Hospital and clinic services account for about 60% of U.S. healthcare spending (while prescription medicines account for about 11%). We will still need hospitals, but they will be much cheaper to staff and run.

Technologies and medicines should become more expensive as the research required becomes more intensive, but AI may come to the rescue there too, with more efficient identification of targets and treatments and with more intelligent patient selection. Healthcare is likely to get much more affordable in the AI era

What about the workers?

The shortage of workers will be exacerbated because each of us expects to work less and less.

Most of us are working many fewer hours than we used to and for a smaller proportion of our lives. In 1870, the average German worked 3,285 hours per year (yes, that’s about 63 hours a week for every week of the year); in 2017, she worked 1,354 hours. Americans had less of a decline – from 3,096 to 1,757 hours. We also have much longer retirements: in 1870, there was no paid retirement for most (the first state payments for older people were introduced in Germany in 1889). By 1950, Americans received social security at age 65; by 2020, it was by 66. Average American life expectancy in 1950 was just over 68; by 2020, it was over 79 years.

The trend has accelerated since COVID. Many late fifty-somethings seem to have tried retirement and liked it; others are less able to work because of long waiting lists for hospital treatment or because they are worried about lack of care should they contract COVID. In the United Kingdom in 2022, there were almost 400,000 more economically inactive adults aged 50 to 64 years than in the pre-pandemic period (out of a total population in that age group of about 11 million).

The closest historical parallel to fewer workers and shorter working lives may be the black death in Europe and West Asia in the fourteenth century. Between 30 and 50 percent of the population died in wave after wave of the bubonic plague – over about the same period that Korea’s population will halve. The remaining workers soon realized the power that they had. It was the beginning of the end of feudal servitude in many places. Despite the best efforts of governments, answering to their rich patrons, wages rose and working conditions improved dramatically. The precedent is bad news for some major retailers and a delivery company that we won’t name because I don’t want my packages to start disappearing.

In the fifteenth century, education became more common and access to healthcare did seem to increase in most places, although it’s far from clear that was a good thing – bleeding and cupping probably did little for productivity. Today, we have the means to make much better use of the people we have, whatever jobs they end up doing.

Health is heavily determined early in life. Over the past twenty years, we have made remarkable progress in preventing diseases of childhood that can impair for life the children who survive them. Some of that progress is now being lost to Luddite anti-vaxxers whose malign influence is reaching from North America and Europe to Africa and Asia, and because of irrational constraints on access to care – infant deaths actually rose in the United States in 2022. Every human life has inherent value, but every child now has unprecedented economic value. We should be spending much more on their health. As societies, we must also find effective ways to stigmatize and marginalize the often well-educated and persuasive fantasists who look back with nostalgia to stone-age societies where people in their thirties were considered unusual survivors.

Older people have to work longer. This is not simple: witness the riots in Paris occasioned by the suggestion that the retirement age should rise very gradually. Older people are much more likely to vote than younger ones, so politicians listen to them. And, except for the political elite, most of the old seem not to want to work into their seventies.

The British Office of National Statistics looked at why those over 50 did not come back to work after COVID. Many of those findings can guide broader policies on keeping the mature productive.

Around one in five of the non-returners said they were waiting for medical treatment; this rose to 35% for those who left their previous job for a health-related condition. The UK health system is particularly dysfunctional but this statistic hints at a much more important economic issue: there is a longevity dividend if we keep older people healthy. As the International Longevity Centre UK has shown in an impressive and fascinating series of reports, “We know that countries that invest more in health see more people working, spending and volunteering and that investment in prevention drives a return. Spending just 0.1 percentage points more on preventative health can unlock an additional 9% in spending by older consumers and an average of 10 additional hours of volunteering across the G20.” (Here is a link to the India report. Those for other countries are on the same website. Here’s a link to something I wrote on the subject in 2022)

Healthy older people do not just work, they spend. Across the G20, which contains many emerging economies with young populations, 56% of total spending in 2015 came from families over 50.

For all the British over 50s, those who had left work and those who had stayed, flexible working and reasonable adaptation were key to staying employed. Those in their seventies probably do not want to work 40 hours a week; they might well want to work for 15, though. Does the job description for a 20-year-old shelf stacker have to be the same as that for a 75-year-old? Probably not, although age may not be the only reason to customize job requirements: in a time where people are scarce and AI is pervasive, maybe every job requirement should be tailored to the health, interests, capabilities and aspirations of every individual?

Among those currently in work, active employer support seemed an important factor in their decision to stay. Again, AI means that this will not require tripling the HR department.

We should note a few paradoxes in the British data that don’t seem wholly idiosyncratic. Those aged from 50 to 59 were more than twice as likely to report mental health problems and disability issues as those aged 60 to 69. Part of that is because some of those in their sixties were going to retire anyway, but part is probably culture. As someone who grew up in the 1960s and 70s, I know the downsides of a “just get on with it” attitude to pain and distress, but maybe we’ve gone too far in the opposite direction.

Big institutional employers seem to do a much better job of supporting older workers than hospitality or personal services firms. This is counter-intuitive. It should be much easier to have flexible, adapted work patterns in a hair salon than in a local authority. Maybe smaller employers are too worried about inadvertently breaking rules on age discrimination or creating grounds for action by an employee who feels disadvantaged? If so, this should be relatively easy to fix.

The populist nightmare

We can keep people employed more flexibly and longer but most societies will need workers and some Africans, especially West Africans, are not going to be able to survive in their home countries. Africans will need to migrate, and the rest of the world will thank them.

My undergraduate degree comes from an Alabama university that was, at the time, the late Governor George Wallace’s pet project (Governor Wallace is the one who barred the entrance to a university to stop the first Black student from coming in and set police dogs on civil rights marchers). Our required reading didn’t quite parallel Harvard’s. In political science, we were assigned Jean Raspail’s racist dystopia, The Camp of Saints. In it, Indians set sail for Europe and seize it – at the time, the scare was about birth rates in India. Africans from the north invade apartheid South Africa, and the Chinese invade Russia. Although it was first published in 1973, the book has had a surprisingly long-lived popularity, with Steve Bannon and Viktor Orbán among its fans. It is the inspiration for many populist memes about the demise of Western civilization.

Among the book’s many flaws is the idea that Europe has always been stable, white and homogenous. Roman emperors were often North Africans or Middle Easterners. This is, in fact, the longest period in recorded European history in which Western Europe has been at peace. The last mass movement of millions of Europeans happened in living memory, when ethnic Germans fled large sections of Eastern Europe after the Second World War. North America is even more turbulent, and the conflict over its transition from Native American (actually, mostly invaders from Siberia) to European and African was still going on at the end of the nineteenth century. For most of history, wars were the main business of states; invasions and enslavement were the main way of sorting out population imbalances.

Raspail is dead, so I’ll risk saying it: there aren’t really many, if any, French people. In Roman times, France was inhabited largely by Celtic tribes who were displaced and assimilated by invaders from the East. The Bretons are Cornish people, displaced by the Saxon invasions of the British Isles. The “Normans” who conquered England were actually Vikings who had come to France only decades before – the same Vikings went on to conquer swathes of Europe: the Kingdom of Sicily was largely run by blond, blue-eyed courtiers.

Even Raspail’s adherents aren’t actually “European”: Orbán’s ancestors arrived in Hungary from central Asia about 1500 years ago. I’ll spare you the rest of the history lesson; the point is that people have always moved to find land, jobs or simply new vistas.

People are moving, and more will move. In fact, we may be competing for them to come. The likelihood is AI will not, in fact, create pools of the unemployed; in most of the world, the population will shrink and age very fast; and we will mostly decline to do what our ancestors did and work until two or three years before we die. Only Africa will have the people we need to staff our security forces, our care homes, our leisure industries and everything else that machines cannot do. Now, we have to figure out how to make this reality as welcome as it should be.